It took me less than four days…

…to make my first faux pas in India. I was at Palitana, on my way down from walking up the 3600 steps (3900 depending on your source) to the reach the 863 (900 depending on your source) temples on the summit of Shatrunjaya hill, considered the most sacred pilgrimage place by the Jain community, a place every Jain aspires to climb once in his or her life. As an aside to my terrible tale, you need to know that a central tenet of Jainism is not to kill any living thing. In fact in 2014, Palitana became the first city in the world to be legally vegetarian, making illegal, the buying and selling of meat, fish and eggs, And in further fact, Palitana had just reopened after its 4 months closure during monsoon, when a stair-climbing pilgrim would have risked squashing untold insects.

So there I was, about half way down, when I crossed paths with a solitary gentleman who pointed to a nearby stone tank, one which I had happened to peer into, just out of curiosity, on the way up. And when I did I noticed the largest, fattest toads I’ve ever seen, lurking in a sliver of shade on the moist mossy bottom step, just above the brackish opaque water at the bottom. So when this gentleman pointed to the tank I made a pleasantry to show I considered us fellow stair climbers, as follows`”Yes, it’s a lovely catchment tank. And there are large toads in it. Maybe we should have us a little barbecue?”

Bernard looked at me with a startled face, as if one of those toads had just plopped down on my head. Too late I realized what I’d said. I cannot describe the look of forlorn dismay my bit of tired uncensored wit generated. I can tell you I skipped as swiftly down the next section of steps as my shaky legs would allow.

Since then I’ve been as careful as possible. I’ve let anyone smear my head with as much or as little turmeric paste as they wanted, My sandals have come off in front of every doorstep and temple, even when I’ve been urged to keep them on.

I’ve acknowledged the little Lakshmi feet inviting prosperity to cross the threshold of homes and shops,

as well as the threads binding peppers, lime and charcoal to ward off the evil eye.

The first half of our trip has taken us through Gujarat, a state unlike any other we’ve been to. Daily the sky was a pale hazy blue, the air hot and filled with dust and smoke as fields of cotton or bushy green castor bean plants (a major cash crop of Gujarat) were harvested, hay piled high on trucks to trundle down lanes in between fields. Toddlers were watched by grandfathers as parents swathed and stacked large bunches of dried stalks for cattle fodder.

In Anand, home of the remarkable Amul dairy coop, instead of having one or two thin cows, families seemed to have 6-8 beasts, all of them sleek and healthy.

Driving across the state the roadways lined with mammoth manufacturing plant, but as we got deep into the Rann of Kutch, both Greater and Lesser, we saw pale sandy ground arid land overgrown with thorny acacia, the product of a misguided government attempt to delay desertification by dropping seeds of this non-native species from airplanes. Without anything to eat it (no giraffes or elephants here), the shrub has evicted most everything that’s native, leading to hundreds of miles of inedible plant-life, which in turn does no favors to the water buffalo and cattle herders.

Yet the essence of what I love about India was evident every time we stopped to walk around in a small village somewhere off the main road. A polite inquiry as to where we could buy a cup of chai would inevitably lead to an invitation to someone’s house. Word would spread quickly, and teachers, relatives, children, whoever was available and otherwise unoccupied, would come over to look at us. And to take selfies.

Sometimes communication would be simple, because a local son, visiting from college, would come to talk and translate. Other times communication was with a smile, headshake and laughter. But it’s easy to understand that cupped hands moved to the lips mean Chai and fingers pinched together, also brought to the mouth, mean food. Burning hot milky tea spiced with ginger would appear, poured into saucers so that it would be sippable quicker. All the men would have tea with us, but never the women, who hung back at the entrance to the kitchen no matter my entreaties.

Tea properly drunk, we would then be asked to stay for lunch. This would be a sharing of whatever our hosts were eating, such as some fresh roti with ghee and a bowl of soft, rich, slightly sour water buffalo milk cheese in Dharampar near Bhuj, or hot thin chapatis with a little bowl of spicy yellow dal heavy with cumin seed in Salwagada, south of Anand, or even a platter of charred peanuts with a bowl of green beans at a self-styled ashram in Devgana, near the soon-to-be embarrassing Palitana.

In the Banni Grasslands of far west Kutch, we were welcomed by an extended family of Maldhari nomads. Backed by a brilliant orange lowering sun, the heavy bulk of black water buffaloes shambled through the scrub toward camp. Tea came from a nearby fire, poured into the ever-present shallow saucers, and a small remuda of fit Marwari horses loped in to join the Zebu cows in the camp enclosure. Children squealed and played with our cameras, the men came ’round to chat with our friend, and behind us was the slap and punch of dough being pounded, from which balls would be pinched and flattened to make roti for the evening meal.

Bernard has been doing a great job of driving, but reports his impression that what’s happening on the roads situation has gotten worse. I differ. It’s as chaotic as it’s always been, still a wild, unpredictable stew of slow and fast, big and small, animal and mechanized, noisy and noisier.

Our vehicle, a Toyota Innova Crysta, is a bit too large for our liking, but in that sense does offer extra protection. Also on the plus side are its Delhi plates, which means no one cuts us any quarter, leaving Bernard to snake through traffic like the native he’s thought to be, and me to stare fixedly at our GPS, spouting lefts, rights and straight ahead at the roundabout with as much sangfroid as life inside a pinball machine with the flippers on overdrive allows.

Writing these newsletters is not just about putting a few impressions into words. They allow me to reflect on what I’ve seen and done, to form connections where earlier I’d seen just jagged pieces with no semblance of a whole, simply to step aside from the daily efforts of figuring out where to go and how to get there, all the while absorbing the extraordinary amount of shifting stimuli around me. By so doing, I suddenly see the simple interest, kindness and humanity in our daily encounters, each an individual bead which, when threaded together, form a bracelet of loveliness and warmth which replenishes my energy more than you might imagine.

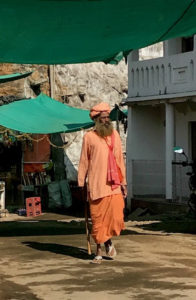

We left Gujarat yesterday, eager to search out the fabled beauty of Rajasthan, its northern neighbor. A dramatic drive to the southern hill station of Mount Abu brought us to a climate zone full of tall trees, with flashes of magenta and pink oleander. At the summit, around the Dilwara temples, sprightly monkeys added their antics to the traffic problems and fringed palms towered above tangles of bougainvillea, while at the mountain’s base, camels used the national highway for their slow and always stately progress. One doesn’t honk at a camel cart. They barely move anyway.