Yesterday I had what I like to call a calorie-free lunch. It was one of those where food comes in the front door, barely stays long enough for a polite howdy-do with my stomach, then runs out the back door faster than you can say “Uh oh.” Such a speedy exit, such lack of civility. I hate it when that happens. This lunch of Ethiopian fasting foods, in a roadside establishment whose appearance coincided with our hunger pangs, was perfectly enjoyable while it lasted, the colorful display delighting both the eyes and the taste buds. Ethiopians have plentiful religious holidays on which they fast until 2:45pm. But that’s not all.

They also fast every Wednesday and Friday, because on Wednesday the Jews held a council in which they rejected and condemned Jesus and on Friday they crucified him. Adding it all up, there are 180 days in the year when fasting is obligatory for everyone. It’s on those days that fasting foods are served. I think that, technically speaking, it would be more correct to call the foods “breaking the fast,” but it’s not my country. Here’s what was on my 14-inch diameter sheet of injera: pale green, braised cabbage, sweet ruby red roasted beets, boiled potatoes made yellow with turmeric and cumin, a mustardy-colored mash of chickpeas with sauteed onion, finely chopped wilted bitter greens, tiny brown lentils with a hint of cinnamon and garlic, orange split peas spiced with more of that garlic and a pinch of berbere. Washed down with a cool beer, I have to say it hit the spot, if only for a second.

We have been through the north of Ethiopia now, which is justifiably famous for its astonishing churches. Some are those marvelous rock-hewn ones, carved into cliff walls in the most impressively inaccessible locations. Others are carved from large slabs of basalt and sandstone until they’re freestanding, separated from the surrounding rock, then refined and hollowed inside.

For the former of the two types, a region called the Gheralta, which is barely south of Ethiopia’s border with Eritrea, is the place to go. With its monumental red cliffs, arid climate, dry packed ground, prickly pear and sparse vegetation, it’s quite like Arizona, but with blooming euphorbia (pink, red, ivory) instead of saguaro. On top and within the reddish cliffs are over 100 rock-hewn churches, so well-hidden that you can’t see them until you’re upon them. That is, if you can even get to them.

Enroute from Axum (Denver’s sister city!!) to Gheralta we took an empty dirt road to the village of Nebelet, which is the access point to one of the least-visited rock-hewn churches, Maryam Wukro. Nebelet was built around a massive slab of rock, so that’s what we drove over to get onto the track we were told would take us to the church some 7km away. Because people in Ethiopia walk everywhere, even on this track that seemed to lead nowhere there were small groups on foot, heading to or from their home hamlet hidden somewhere in the rolling scrub hills around us. Groups of people are on all roads, of course, and what’s nice about them is that they’re all talking to each other. It’s satisfying to be reminded that there are still pockets in the world where texting and twittering haven’t taken over and people still converse.

After 3-4km we felt uncertain about our direction, so stopped to ask the way. The fellow we queried, nicely dressed in white shirt and trousers, offered to show us. This sounded like an excellent idea. The trouble is, one can’t always detect everything about a fellow when chatting through the window. As soon as our new friend closed the car door it was apparent that he was accompanied by a truly sour-smelling, acrid type of odor. It was almost unbearable. But we needed him and so had to just breathe lightly for awhile.

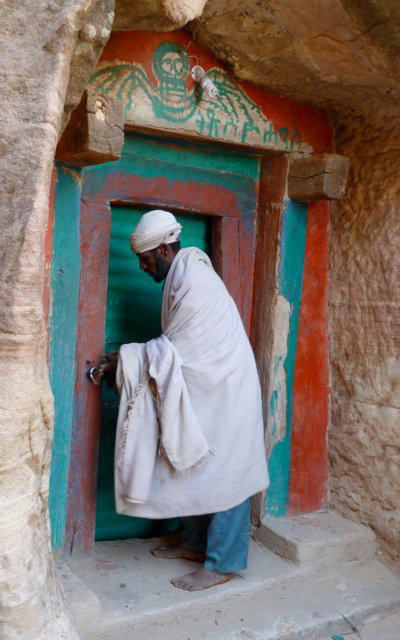

After another 15 minutes which entailed driving down the by now usual steep rocky track and crossing the usual rocky river bed, our malodorous friend signals “That’s it,”, pointing to two holes in a limestone cliff. A grizzled old man swathed in blue with a stained white turban wrapped around his head appears as soon as we cut the engine. Considering his divine role, this was one surly and demanding priest. He knew he had us by whatever priests believe they have you by, since we’d driven all that way (the 7km took half an hour to cover) and were unlikely to go back with our quest unsatisfied. We paid up and were lead to the cliff wall, where we had to stoop to get under the low hole. Inside it is dark and cool, natural light filtering in through the door hole and some small high windows. Although the interior is simple, it’s astonishing. There’s all the basics one expects in a church, including columns, lintels, romanesque arches, and domed ceilings 35 feet high. Nothing’s been constructed. It’s all been carved out from the solid rock mass. Chisel marks from 1500 years ago are evident on all surfaces of the white rock. However, between the level of a person’s hand and their head, the columns have acquired a slick, shiny brown patina, as if someone’s painted on a thick coat of dark varnish. They’ve been oiled by centuries of lips kissing the stone, foreheads bowing on the stone, cheeks rubbing the stone, hands caressing the stone, as people strive to get extra close to divinity and blessing.

The next day, with a hired guide, we head for the rock-hewn church of Abuna Yemata Guh. Our guide points to a ‘V’ in the 1000-foot rosy cliff we’re standing below. “It’s up there,” he says, and my stomach does an about face and tries to head downhill without the rest of me. I can tell is the cliff’s near vertical, but apart from that I can’t even see any holes that would identify where the church has been carved, let alone a discernible way to get up there. We start up a rocky path which gets progressively steeper and more exposed as we climb. My stomach’s shut down and now my head is doing strange dizzy dances that result in me being grateful for the firm grip our guide offers when we have to sidle across narrow ledges smoothed by thousands of religious feet. I force myself to only look up. If I make the mistake of looking down even for instant, I will freak myself out and advance no further.

At a small grassy opening we come upon the church’s priest, who’s on his way up to open the church. He does this every morning in one-size-too-big plastic sandals. I guess his age at mid-sixties, figuring people here look older than they actually are. He shoos flies away and chuckles. In fact, he’s eighty-one years old. I suggest he guess my age. He returns the favor by guessing that I’m thirty-five. After a brief rest he disappears up the path. We clamber behind. Soon we’re standing on a dirt ledge that’s about 4 feet deep, which juts out below a vertical spot. It’s not a very long vertical spot, maybe 75 feet in total, but it’s utterly exposed, just dished depressions in the cliff face for one’s hands and feet. I take a purposeful two steps up and freeze. For the life of me I can’t imagine how, even if I could go up there, I”d be able to get down. “Can’t do it,” I yell to Bernard. Over the protestations of the 3 hangers-on who’ve joined us and who gesture they will support my butt and feet so that I will not be in danger, I cringingly lower my feet back to the now seemingly vast ledge and send Bernard up without me. While I wait, a young man appears, carrying a gallon bottle of water. He blithely steps up those modest footholds, using only one hand, as if he were climbing the escalators at Macy’s. Bernard reports that Abuna Yemata is gorgeous: intricately carved, with vivid paintings that, all told, make Maryam Wukro look like the princess’s plain stepsister. I’d kick myself for wimping out, if I weren’t concentrating so hard on keeping both my feet on the ground.

At 2:30 we go out again, the sun beating us about the head. We’re off to rock-hewn church number three: Yohannes Maequudi. This one, too, is invisible until you reach it, but the way up is simply steep; the guide must have realized I don’t do vertical. We zigzag up through rock-walled terraces built by villagers to plant trees for a gov’t program aiming to reforest parts of Ethiopia. A shrill horde of small village boys betray their true roots as mountain goats as they run and jump along the trail, chattering and giggling non-stop. After about 45 minutes we top out on a broad, open, grassy pass, a lovely spot with a stirring view of the other cliff massifs. Apparently the church is right above us, but so cleverly hidden I can’t detect it.

Entering the walled forecourt of the hidden church , we’re greeted by two old ladies who shyly offer us blue plastic goblets of what they’re brewing. It’s the same barley-based liquor beer which Assefa offered us at his farm in Bahir Dar. This is one of the things I love about an extended trip in a particular country. I have the opportunity to bump into things I don’t like over and over again. Not that I’m close minded. Far from it. I’m always willing to try something again and again. Still, it’s oddly comforting to know ahead of time that whatever it is I have to eat or drink is something I already know I don’t like. It takes the edge off the strangeness of it all, makes me feel like I’m an insider.

One of the ladies is wearing a heavy, faded yellow flower-print dress, made grey with age and dirt, that reaches to her ankles. The other, taller, with huge wide-set eyes that droop down at the corners, is in a long purple paisley dress. Silver earrings decorate their ear lobes in several places. The two old friends show us where they’ve been doing their brewing, inside a hut made of sinuous branches blackened by charcoal smoke from eons of fires. Deep in the shadows are three clay urns, big enough to reach my waist, reclining at a slight angle next to a back wall. Each is filled with a liquid that will ferment for three days, at the end of which it will be offered to the hundreds of celebrants who will come to the Yohannes Maequudi church to celebrate the name day of its saint: St. Yohannes.

At the time of our arrival, the liquor’s been fermenting for just one day. Though it’s unfinished, I have no doubt their version is far better than what I tasted a week ago. I also have no doubt that it’ll make me gag the way the first version did. Still, I cannot disappoint these proud and gentle ladies, whose job it is to make the liquor for St. Yohannes Day every year, as well as any time in between that such a tipple is required for properly celebrating anything.

I gaze without fondness at the milky, olive green liquid in my glass. I ask for a second cup and pour some of it out. One old lady smiles at me and nods, thinking she understands what I’m doing. She grasps the glass and offers it to Bernard who, of course, declines. She shrugs as if to says, “Men, what can you do,” and pours that portion back into my cup. I immediately pour it back out into the cup she’s holding and she, a real swifty, pours it all back into my glass again. She wins. I take a sip. It’s a strange tasting brew, somewhat bitter, a bit chalky, with a thick sourness that’s as reminiscent of beer as vinegar would be of a fine aged Bordeaux. I ooh and aah and smile and bow. I hand her the full glass back and say brightly, “So, where’s that church?”

We sit on the dry grass of the knoll that tops the sandstone cliff we’ve submitted, under the welcoming shade tree in the courtyard. We’re waiting for the priest to arrive, who lives in the next village. Birds twitter. Tin wind chimes tinkle in the breeze. It’s about 4:00 and the sun now is pleasantly warm. Suddenly the priest is there, all bows and apologies for making us wait. He’s run all the way. He isn’t even out of breath. He leads us around a bulge in the limestone outside the courtyard and there are two telltale holes, these ones with painted tin doors, one sky blue, the other pistachio green. I duck inside and once my eyes have adjusted to the dusky light, I can make out a beautifully proportionate interior, perhaps 30 feet long, 20 feet wide and 25 feet high. It was carved out of the rock in the fifth century and is painted with simple frescoes on all walls and the ceiling. The depictions of your standard saints and such, is crude, almost child-like, with little attempt at symmetry. Chisel marks remain obvious on the white stone, like claw marks by a bear, because neither wind nor water ever touch them. I can’t say how this church compares with Abuna Yemata, I can only say I was glad I was there.

We took a break from the churches to head into the Danakil Depression, the desert which is home to the purportedly fierce and unfriendly Afar tribes, the ones whose Kalashnikov-toting brethren we’d encountered earlier in our trip. Our objective was to go up the volcano Erta Ale, which has an active lava lake near its summit. This is not difficult to do, but requires some organization and a willingness to shell out lots of birr (Ethiopian currency) whenever asked. The agent who booked all our hotels in Ethiopia was supposed to take care of this, but things got confused and we wound up with the extra car and driver he’d sent “for our safety,” but with insufficient cash to pay off all the outstretched palms and I don’t mean the tree kind. We didn’t make it to Erta Ale, but we did have a great 24-hour experience anyway.

For one thing, we drove from the cool, forested height of about 7,700 feet to 400+ feet below sea level. Brunhilde rattling and banging around hairpin turns and over sharp stones, we descended into ever-scrubbier, scruffier, dry terrain. We passed hills made of tilted layers of ochre, yellow and beige rock. Thorn trees abound. Huts are made of gnarled branches lashed together with twine. The meaning of “dirt poor” is rudely evident here, as the people barely have dirt to grow things, let alone water to help anything flourish.

After 2.5 hours we reach the Afar outpost of Bera-ile, where we are to get permits for Erta Ale and Danakil generally. The village itself looks like a heap of sticks and stone that have lost their will to stand up straight. Afar, with their teeth shaved to points (this is a tribal thing), lounge about, eyeing us. When they open their mouths to smile, their eyes stay frowning and they look like vampires. Their normal tone of voice strikes me as full of vehemence and imperatives. But maybe that’s only because all the sharp pointy teeth are making me uneasy.

Things don’t move fast. One person essential to our progress is busy praying in a mosque (all Afar are Muslim). Someone else who has a particular key must be found and a boy is sent looking. I don’t even check-in with my small stash of patience, because I know to do so would only lead to catastrophic results. I eye the flies, study the ground, wonder how many fleas are flexing their knees, preparing to leap onto my legs for a blood feast. There’s much shouting, palavering and arm waving. Eventually the requisite permit is written up, and we must only wait for the the two armed guards and local guide who have been foisted on us to appear.

To pass the time we decide to do something meaningful: eat. The local cafe huddles behind us, a crude hut w/dirt floor and 8-inch high benches on which people squat.

The food on offer is shiro (boiled, seasoned chick pea flour) with injera. I don’t expect Bernard to eat any. The cool rubbery injera arrives, in the center of which is a thick glistening dollop of orange-brown shiro, topped with a diced sprinkle of purple onions. When I explain to Bernard that he’s to tear off a strip of injera and use it scoop up some of the mash, he seems to beg the heavens to please send him down a fork. Then, to my amazement, he follows my instructions, stuffs the whole mess in his mouth and says, more or less, “Yum.” He likes it! I would have fallen on the floor in astonishment had I not already basically been sitting on it. While we eat, four Afar come in and get their own shiro order. They glower at us more than we stare at them.

Finally we’ve assembled permits, guide and guards all in one place, the latter personages to be transported by our agency’s driver along with as many other strays as can squeeze into his car. Bernard and I take off, heading for Hamed-ela, the last settlement before the empty desert. When we leave, I see the driver yanking all the extra Afar out of his car, like someone burrowing in an old trunk, flinging garments left and right. The Afar exit reluctantly, spewing venom at him, enraged, entitled, their bundles bouncing in the dirt. Quicker than he can jerk them out, they grab their bundles and dart back in. As we drive by, I make out at least 8 of them squeezed in the car, with a dozen more encircling the vehicle, everyone shouting and shaking their fists at each other.

The road heads down, down down, flattening out into brown, rubble-strewn nothingness. Hamed-ela, when we reach it after about an hour, is a ragtag assortment of stick huts in the dirty sand; a level place for each has been created by clearing the rocks that cover the ground, using them to demarcate an alley which is now used as the defacto road.

A strong wind blows without pity, raking the ground, tugging at the scraps of plastic tarp and sacking that make up the hut roofs, shredding the fiber mats shoved in between the stick walls. A goat clambers on one rooftop, testing shreds of plastic sacking for edibility, pulling out loose strands which then whip about in the wind….goat as flag-bearer. The sky is heavy with low grey clouds, the air sulky and humid. This Danakil desert makes the Namib desert look like a veritable garden of eden. The landscape is flat as a nickel squashed on a rail by the 3:10 to Yuma, and just about the same color. It’s barren, not a tree, shrub nor blade of grass growing. But it’s not empty.

In the distance we see a string of dots. As they get closer we realize these are the salt caravans, camels carrying salt bricks cut from the salt flats 20km away, just as they have been for centuries. The salt caravans end at the main market in Mekele, a week’s walk away. As we watch, the first of the camels reach us, then passes by, silent, tied head to tail, following the same trail their predecessors followed hundreds of years ago when salt was so valuable it was used as currency.

More camels come, and more, interspersed with troops of hardy, overburdened, salt-bearing donkeys. It’s a snaking brown line proceeding in slow and stately fashion over a ground of black rocks, stretching into the grey distance until it tapers off at the far horizon where the sky has turned a faint pearl white. Each camel carries about 200 pounds of salt, the bricks lashed to crude wood supports sitting atop a ragged pile of soiled pads. Every 10-15 camels has its own 2-3 Afar minders, thin men striding with a goat skin of water and a slab of hardtack tied up in a rag, taking the camels to market one week and leading them back to the salt flats the next. With a grunt or a cough, they keep the camels in line, and move them forward.

We sleep that night in a stick hut, putting mattresses on charpoys. The wind is a constant presence, but the night’s surprisingly warm and pleasant. We awake to drizzle, which turns the desert into mud soup, very sticky and tricky to drive in, the sort of treacherous surface where you know without saying it that if you stop, you stop for good. Bernard is at his best in these trying conditions, wrestling the steering wheel into submission as we slither and slide through the greasy mud. Then we reach hard-packed bronze-colored salt; it’s peeling backwards in great, flaking, razor-sharp scabs. Finally I can breathe when we emerge onto an eggshell- smooth white salt flat.

We walk up a rocky moonscape to behold the mineralized beauty of Lake Asale, its lime green waters fringed by canary yellow sulphur deposits, crystal tubes belching clouds of steam smelling of rotten eggs, the ground around a crunchingl carpet of crinkly, crumbling iron oxide the color of dried blood.

On the way back to Hamed-ela, we stop by the salt flats, where men work with crude tools to chop blocks of salt out of the crust, then trim them to the standard size and shave off any crust that’s not salt. These are the counterpart to the caravan walkers, the ones who stay behind and prepare the salt slabs for transport. The labor is horrendous and backbreaking, since the salt crust they’re cutting floats on water, so the men’s skin is constantly soaked in abrasive, saline solution. Thousand of camels are resting around the salt works, their backs exposed, showing terrible chafing from the rudimentary pads and stick braces that are used to lash the salt bricks on. I don’t know which is worse, working the salt, traveling with the camels, or being one of those camels.