Tibet is not China, much as China wishes it were. If Tibet were China, then China would not need to exert so much effort to convince others that it is. Proof of this is visible on every street corner in Lhasa, where police or soldiers stand at motionless attention, watching, surveying, making known by their uniform and very presence that the Chinafication of Tibet, though well-underway, is an artificial implant on the Tibetans which still refuses to take.

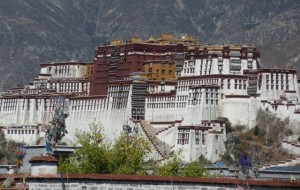

I wish I could have seen Lhasa even just 15 years ago. Sadly, most of what I’m told Lhasa was is now gone, replaced by cookie-cutter buildings in the boxy, monotone China style. Around Jokhang Temple, which dates back to 642AD and is considered by Tibetans to be their most sacred and holy temple, there are squadrons of soldiers marching through the square, drilling, pivoting, glaring, strutting in their camouflage outfits, rifles at the ready. Two behemoth urns at the temple entrance billow with pale grey plumes from repeated offerings of incense. It’s as if their benign, squat presence says “You can march to your heart’s content, but long after you’re gone I will still be here gently smoking, as I have been for more than a thousand years.

In the surrounding courtyards below the high temple walls, Tibetans with heavy coral and amber necklaces, and large bone and turquoise beads woven into their black braids, prostrate themselves hundreds of times over in fervent prayer at the temple entrance. The soldiers are a continuous heavy-handed reminder of just who’s in charge here, but honestly, do they actually expect a yak herder to come round the bend in a tank to take them on? Still, woe be unto anyone who photographs the military too obviously. My photo was taken from the roof of the temple.

We are told that more and more Han are being located in Tibet, to make the population more heavily Chinese. Indeed, many of the shops we pass are Chinese-owned and operated. But still, Lhasa has a feel to it that strikes me as firmly not Chinese. Am I knowledgeable enough to say why or how that is? No. But driving through Tibet for the 4-5 days we’re there, observing people with distinctly non-Chinese features, eating non-Chinese foods, looking at non-Chinese architecture and lifestyles, I have to believe that there’s a strong and resistant Tibetan strain that remains defiantly non-Chinese and will endure.

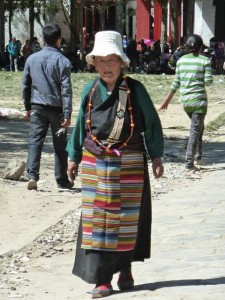

There is a distinct feeling about the Tibetans, an openness and a smiling sense of welcome that I did not feel from other peoples in the western region of China that we traversed. I imagine the Chinese are only too aware of this, hence the oppressive military presence like a continuous slap in the face to the Tibetan people.

In Shigatse, south of Lhasa, the large city park is full of locals and country people sitting on the ground, waiting for a dance performance to begin. It’s as festive as a country fair, with food booths everywhere, (fabulous spicy, crispy homemade potato chips are my personal favorites), bright plastic toys and balloons for the kids, large family groups clustering under scruffy trees. There’s card playing going on accompanied by sharp shouts and much gesturing which might be a way of pointing out a cheater or perhaps emphasizing a win, lots of imbibing of tall bottles of beer which, from the red faces and squinty, puffed eyes of the drinkers, might in fact contain chang (barley alcohol). There’s loud slapping of dice onto mats in a special gambling game which I can’t make heads or tails of. In short there’s the generous bubbling mix of patience and excitement that you’d expect at any local gathering. There, as well as on the way to Everest Base Camp, where we drove slowly past or through many Tibetan villages, I am relieved to see that many aspects of life seem to go on much as they have since forever.

Women wear long heavy serge skirts with a short striped apron, a heavy wool scarf wound around their head, cheeks chapped a bright red from the sun, wind and cold of these altitudes. Villagers still have thick embroidered red felted wool boots on their feet. Barley is still the main crop and dung the main source of fuel and heat on the vast plateaus that are high above tree line. And the traditional colors of white, red and black still adorn all the houses I see. In villages closer to cities, the Chinese have mandated that new houses be constructed of cement block. But out in the countryside, the houses are still flat-roofed and made of mud brick, with large inner courtyards and a stable on the ground level, where the presence of livestock generates not only warmth for the family living above but, unfortunately, lots of flies as well. Rakes and other hand tools are still made from branches and sticks. A cluster of reeds supports prayer flags that are continuously aflutter from each corner of each roof, with a solitary gold-starred Chinese flag as a token reference to the current powers that be.

I would love to return to Tibet. I’d spend time on the more remote roads which lead toward sacred Mt Kailash. That area also is the source of India’s great Brahmaputra River which flows east and then south, curling eventually into Assam, and from there merging into the Ganges Delta before emptying into the Bay of Bengal. When we were last in Assam, on our way to Nagaland, we drove along the Brahmaputra but never really saw it, as it was obscured by factories and gravel pits and all sorts of unsightly things. It’s one of those serendipitous connections of travel that last week I should find myself driving along a beautiful, sparkling green/blue river, only to discover by a glance at the map that what’s known in Tibet as the Yarlung Tsangpo, is in fact that self-same Brahmaputra I’d wanted to see three years ago.

And so this particular journey ends as it should. With a few days in a now somewhat familiar Calcutta, with memories of some stupendous scenes and driving, with the oddity of connections neither sought nor suspected, and with a momentary wistfulness that this trip is now over.

-Dina