Staring at the mare, I feel something stormy and perilous; there’s a barely suppressed turbulence about this seven year old mare that warns “Watch out.” I peg her for a survivor not only well-settled in her ways, but quite clear on what she needs to do to stay alive. She’s managed by her own wits for a long time and is used to getting her own way, which is not a wonderful thing for the human who plans to ride her. What’s niggling at the back of my mind is that the only person she will really be able to trust is the first person who gentled her. And that person is a felon locked in the state penitentiary for a long time to come. Asking her to transfer that trust to someone new may be one ask too many. But what do I know. I’ve only ever had a few horses in my life, none of them mustangs. I can’t exactly hold myself up as a paragon of horse intuition.

I’m not the only one assessing things. The mare seems to take my measure instantly and dismiss me just as fast. “You may have me,” she seems to say. “But it’s another thing to tame me.” Watching her watch us with suspicion, standing as she’d been taught to, but not liking it overmuch, I have an inkling her age won’t bode well for us. Still, the mare’s uncertainty draws a burst of empathy from my heart. I know she’s thinking “Where am I?” Then “How the hell did I get here?” Followed by “And what the %&@# am I supposed to do here?” And lastly, “How do I get out of here?”

I shove my hands in my pockets so that Bernard is the one who has to hold the mare’s lead line while Carol prepares to get the second horse out. Stepping up into the trailer, she tosses these words over her shoulder, “That mare’s edgy. She wasn’t too happy about getting in the trailer. And from the sounds of it, she didn’t enjoy the ride much. But this little gelding back here…. He walked right in and I don’t think he’s moved a muscle since.”

I shiver. That moment in Cañon City when I succumbed to buyer’s guilt is coming back to haunt me. Standing here now, it feels like the stupidest move I’ve made in a long time. My present reality– that having two wild horses on the premises is more than I can handle– is dawning too late. “Maybe he’s dead,” I think. This strikes me as a possibly optimistic outcome. I’m not savvy enough to train even one of these animals. It wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing if one of the two horses expired.

I prepare myself for what may be the sight of my other horse lying unmoving on the trailer floor. Because of his association with me, his life after being rounded up didn’t even last a year. My visions of horse accomplishments seem dead on arrival, too. I experiment with feeling wanly remorseful, don’t like it and am thankful when another frantic neigh from the mare snaps me out of my unproductive tussle with anxiety.

Hinges squawk again and the trailer door bangs against the side. It’s an overture for the Big Reveal, the moment when number 6491, that recalcitrant steed who’d taken three times longer to train than any other mustang in the Wild Horse Inmate Program (WHIP), will be seen for the first time in all his gentled, domesticated glory.

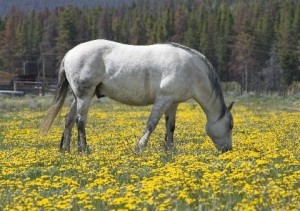

Carol opens the interior divider and there he is. Number 6491 stands calmly, four legs firmly planted, long grey forelock shading perspicacious black eyes. As he obligingly follows Carol out, his snapping hoofs resound deafeningly on the steel trailer floor. It doesn’t phase him one bit. He’s self-possessed, pleased with himself, as poised as a debutante making her entrance into society.

I take 6491‘s lead rope from Carol and she takes the red roan mare from Bernard, and all three of us walk the two mustangs to the corral where they’ll live for the next week. Only time will tell if the old pine rail fence will be stout enough to keep them separated from our other horses as they get to know each other.

The mare I name Willow, as much for her color as her supple, pliant lines. Bernard offers a name for the gelding, one that in retrospect is eerily prescient. “Call him Scout,” he says. “It’s small, a short name, just like he is.” But I see it another way. Scout: the one who goes ahead, finds the safe way, and brings you home.

Investigating the corral perimeter, Scout pauses for a minute to look at me, his gaze direct and appraising. He raises his head high and a quick breeze lifts his coarse, heavy mane as he issues a piercing, poignant whinny, calling a long-lost herd, announcing that perhaps now, finally, he’s where he belongs.

If you’d like to continue with this story, click here.