-

Archives

- November 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- November 2015

- February 2015

- July 2014

- June 2014

- October 2013

- January 2013

- October 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- November 2010

- September 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- March 2009

- February 2009

- March 2008

- February 2008

- November 2006

- August 2006

- March 2006

- August 2005

- July 2005

-

Meta

Monthly Archives: February 2015

Rubies Are Red, Sapphires Blue

Some See Rubble, Others Riches

“I’m frightened!” Saw blurts, his dark eyes seeming to strain to focus on something far behind my back. Detecting alarm on my face as I try to decide if I should be concerned, his shoulders start to heave, his head nodding in staccato bursts. Saw is throwing a major laughing fit.

“Last night,” and he nods abruptly again, as if to confirm this really happened, “I’m awake. Very dark! 3a.m.!” Saw speaks only seldom and when he does it’s in compressed sentences, with extra emphasis on every one, as if each is a declaration of global import. He also often repeats himself, in part, I think, to make sure his foreign listener understands, and in part, perhaps, to confirm to himself that he has, indeed, said something out loud. “3a.m.!!

His nodding shifts to double-time, betel-stained teeth visible in his wide open smile. “Feet gone!” He pauses for maximum effect, leans forward, his eyes boring into each of us in turn. “Stolen!”

Here he utters one of his place holder pronouncements: “So?”– a rhetorical inquiry to give himself time to formulate the next part of his story in English.

Looking around wide eyed, Saw says, “I think, ‘Ghost took them!’ He glances at each of us as we search warmth from a small china cup of tea in the open air of a chilly Mogok teahouse. “Ghost!! So? I’m frightened….because…..no feet!!”

Now he has to set down his teacup because he’s laughing so hard, shaking his head in disbelief. “Last night too cold!”

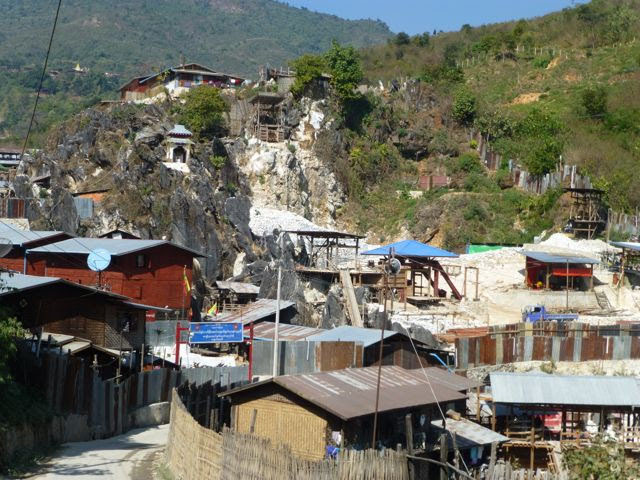

Mogok, a prosperous mountain town of low-rise houses and plenty of monasteries, sits at 1000 meters. It’s hot enough for a tank top and sandals during the day, cold enough for cap, wool top, sneakers and fleece jacket at dawn. The hills that rise from the town are salted with stupas, their covered access stairways hugging a ridge like scales on a dragon’s back. Beyond the stupas rises a ripple of higher forested ridges, the green canopy dotted here and there with a tree in effervescent lavender blossom, or a tall shrub flowering in a froth of white. Look closely and you’ll notice large patches missing from the forest, as if a green scab had been scraped off, revealing the raw, pale orange earth beneath. These are the ruby mines, from which over 70% of the world’s rubies are extracted, mines where rich veins of quartz are dynamited far below ground, to release tons of commercial grade gems as well as jewels of the

rarest size and quality.

As some of the first foreigners with permission to enter Mogok, we are the lone whites on the bustling streets. Our first stop after Saw’s comedy routine is the Thar Phan Bin gem market, on a narrow side street near the town’s central roundabout. This morning, because of the cold and because it’s midway through the Full Moon Festival, most of the shop doors remain closed, the small time opportunists absent. Most buyers and sellers are elsewhere, either recovering from the 3:30a.m. prayers at the main pagoda, or preparing for the coming night’s festivities. So we drive out of town, to the mining village of Ka Doke Tak. The route takes us up into those forested hills, past small clusters of teashops at which scooter-riding ladies stop for a neighborly chat or to pick up the day’s necessities at the local ‘grocery store’.

The pale dirt streets to the mines of Ka Doke Tak wind steeply up from the village’s market place, host most days to a TAR PWE ( which means brass plate on which gems are displayed), the informal street market where successful scavengers sit on low stools unwrapping squares of notebook paper to show the tiny raw gems they’ve chipped from quartz waste deposited by each mine in truckloads, free for anyone to pick through.

Most are women, who may quietly draw up alongside a stationary visitor to show a few pinkish-red grains, or perhaps a lump of quartz….rubies in their raw state.

Along the road up to the mines, women squat on piles of sparkling white quartz, faces shaded by conical bamboo hats. Each woman has friends who work the slap heap with her and each such group has its designated pile, just as a drug dealer would have an acknowledged street corner, upon which others do not encroach.

The women are Lilliputs squatting on Gulliver’s giant pile of sugar, except the quartz gleam is brighter, harder, denser. With one quick movement a woman carves out a small heap with a piece of tin, checking through the seed-size grains with nimble fingers, as if searching for nits, then drawing in another mound. Every day more is dumped, a snow white pile of endless glittering promise.

We try for our first unannounced mine visit. The one we choose. Saw tells us, is operated by the Chinese. Its high, heavily dented tin gate under a flag-sporting archway, blocks our view of the yard inside. Razor wire discourages clambering over walls. As we lurk hopefully near the entry, a security guard unlocks the gate for an approved person, but clangs it shut for us. “Not easy here,” says Saw, more expressively than usual. “Chinese owners,” he continues quietly. “Not want you see.” He clasps his hands behind his back and ambles up the road.

But I’m still curious, so I linger behind. On either side of the entry gate are two newly built watch towers, just like on Hogan’s Heroes. They’re empty, though the arc light in each implies they may be manned at night to prevent thievery. When Saw saunters off I dare to peer through a hole gashed in one gate panel. I can see an orderly dirt quadrangle, with men under tin-roofed sheds squatting in front of piles of ever smaller pieces of quartz, the essential material in which rubies, and sapphires, are found. I hurry to snap a photo.

Perhaps the little zoom lens of my camera, which I’ve shoved into that hole, betrays me, because through the view finder I see a man in camouflage pants quick-stepping my way. I do my own quick step up the street to rejoin Bernard, palming my camera into my pocket, feigning interest in the view ahead.

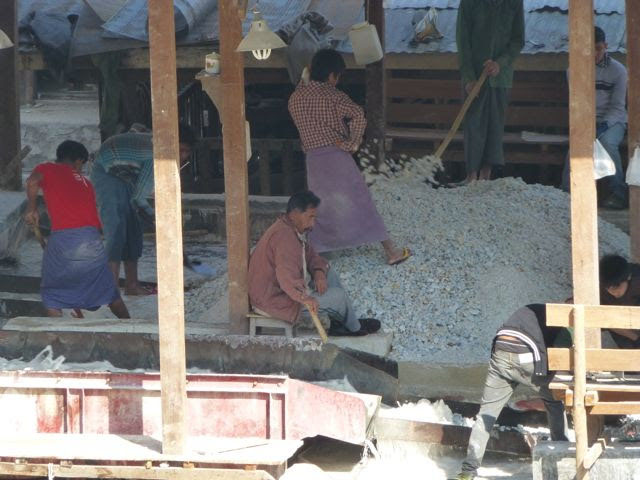

In one mine, 17 men report for work every day. Seven stay on the surface doing an assortment of support jobs. Two squat on a grey pile of explosive compound, which they sift into dynamite tubes and top off with detonator charges. By hand.

The mine’s working surface is a cobbled-together wood platform with two 5’x7′ openings, each with a pulley system and cables descending into the black. Twenty feet below this platform a ten-rung wood ladder made of limbs and branches is visible, the first of many such that a miner will scale each day to get to his designated level. It’ll take him 20 minutes to descend ladders to 1000 feet, perhaps double that to clamber back up.

Down one go a quartet of black buckets full of concrete, to be returned minutes later for a refill. Up the other comes a quartet of black buckets to be filled with quartz rocks the size of footballs. Two two-man teams staff these portals, through which rock is uploaded from the ten lateral tunnels bored at 100-foot intervals below and cement is download to reinforce those same tunnels. Four buckets come up at a time, are detached from the pulley and lugged to a truck 10 yards away, where the contents are dumped into the bed. Not more than 5 minutes passes between bucket arrival, detaching, dumping, reattaching and sending the bucket ensemble back to the depths. The buckets arrive every ten minutes or so.

The shift supervisor, Ko Nan Mg, grew up longing to work in the mines like his father did. He tells us he remembers peering into the mine where we’re standing when he was six, wishing for the day to come when he could join the men behind the gate. Now he’s thirty, and has done every job this mine has to offer. A man tends to start at the mine around age 16, and if below ground, will be in an environment in which water drips continuously, to such an extent that during the April to October rainy season the mine shuts entirely. Barring accidents, he may work at an assortment of mine jobs for 45 years.

These are not bon-bons…..

While we talk with the supervisor, the mine’s manager sits nearby, playing with a litter of puppies. A fuzzy black and beige one clambers at his pants leg. Slowly placing his hand under its plump belly, he scoops it up gently to his face, kisses it on its black nose, sets it tenderly back with its mates.

Further up the road, a young man stops his scooter and steps into a narrow paved drain which carries the shallow bluish sluice from a mine above. He scoops out a light handful, spreads the grist on the wall beside him and quickly stirs through it. Nothing. He scoops, dumps, spreads, stirs again.

Above, behind a 20-foot tin and bamboo wall, a Chinese track hoe shovels bucketfuls of quartz rock into an immense funnel. The rocks bang onto a conveyor belt, rattling along to a crusher, smaller pieces clattering onto vast mats on which sit sorters, checking all, removing a few, pushing most over the edge into the rejects bin, from where dump trucks will bring them to those favored street corners, for the unemployed to sift through.

Returning to Mogok mid-afternoon, we order fresh avocado juice (for me) and beer (for the others) in a cafe brightened by shelves of potted petunias. It’s a happenin’ place and the terrace up top is packed with clusters of teenage couples gesturing with cell phone in hand. The place has the air of a 1950s soda shop, except the muscle cars are motor scooters and all the occupants are Burmese. Even though it’s 3pm on a hot sunny afternoon, the girls are in long slinky dresses and furry pink jackets, hoods tied by pompoms a cheerleader would envy. The boys wear skintight jeans and Converse knock-offs. Their T-shirts betray the local maker’s incomprehension about the world outside Myanmar: Real Chelsea, Harley University, I ‘heart’ Hello Puppy. Each sports the latest mountain town pompadour, complete with a russet swath tinted into their black hair.

Most of the boys drape a possessive arm around the girlfriend du jour, who snuggles with acquiescent delight. Noodle soups and curries arrive, and the boys fall to, while the girls pick daintily at a morsel, suck from a straw standing upright in pink sludge which must be a strawberry shake. They hunch forward shrieking with adolescent laughter, collapse back against the protective side of their boyfriend to catch their breath.

Back on the mining village corners, the quartz heaps beacon, the sifting continues. Because in Ka Doke Tak, one may be poor for a lifetime, but rich in a day.

Posted in Burma Again, Dispatches

Leave a comment

Burma, appetizing

Driving our several thousand kilometers through Myanmar’s rural areas I saw a lot of livestock. Because I love animals I can’t help myself…my head swiveled for a split second judgment on the condition of every one we passed, no matter how far out in a field, or how much underwater.

Happy for me and my nerves, nearly all the zebus, water buffaloes, horses, pigs and chickens looked plump, glossy, well-feathered, and carefully tended. And I saw a lot of them, hundreds, every day, all day.

Now I have to tell you that the air con quit cooling half way through the trip, just as we left the coolest part of the country for the hottest part. I attributed this to a momentary lapse of attention from our banyan tree. The upshot was windows open to all the, ummm, music of rocky, dirt roads driven at appropriate speed to get us past the slow combis, trucks and motorbikes. All those motorbikes, by the way, have created a demand for mom&pop fuel stations, where they’ll stop without any sort of signaling, even if their bikes had turn signals….. They’re everywhere, as anyone with an empty water bottle can set up shop. Bear with me, as I really am going somewhere with this story line, despite the slight side tracking.

Since Myanmar pavement is only one and a half cars wide,we did a lot of veering off it, chattering onto the dirt time and again, dodging oncoming bullock carts, school children and other things one should not hit.

To focus my mind (I swore only once and immediately regretted it), I found myself making up riddles using the most obvious subject to hand: animals. These are painful as well as somewhat embarrassing; I expect they’ll generate the groan heard around the world. But I’m not above humiliating myself by sharing them, just so you can see what really happens after hours in the car. If you give up and want the answers , check the end of this dispatch.

1: Why did the pig cross the road?

2: Why did the Englishman marry the psychic pig?

3. Why did the cows cross the road?

4. What did the water buffalo shout to the chickens hauling his cart?

But, back to proper dispatch material: Driving from Mogok to Tagaung, we stopped in Te-Z for tea and snacks, as was our mid-morning habit. Saw, our passionate and resourceful guide, knowing of our interest in Myanmar’s WWII history, asked the teashop owner if she knew any area war relics. I imagine her response was, “Do I? In fact, I have a live one!”and she left us to our happy fried snacks. Ten minutes later she returned, walking slowly beside an elderly man: Mr U Kyaw Shin, a small dapper 91 year old dressed in a grey shirt, burgundy sweater and navy blue longyi.

Through an hour of story-telling translated by Saw we learned he was 19 when the Japanese arrived in town, on their push east to the Chindwin River. Most people in Te-Ze fled; he found a dictionary and learned Japanese. “What were they like?” I asked him. He laughed ruefully, all three teeth showing, dark eyes crinkling into his fine black brows. “All soldiers are the same!” he said, having lived not only through the occupation, but the military regimes that followed.

He and three others were taken with the Japanese as servants, as they pressed rapidly east following the British retreat. After Flying Tiger aircraft (locally called Twin Buffalos) flew over, the Japanese would say, “We will lose. We know this.” As my questions unravel more of U Kyaw Shin’s story, people gather round, listening rapt and silent to his tales from 70 years ago. I imagine the younger ones have no idea what had happened to him. His capable carpenter’s’ hands, now like stones wrapped in dark brown parchment, gesture vividly as he recounts his stories. Only when he says, “I am the only one of the four who made it home,” do they drop to his lap as he falls silent.

No trip would be complete if I didn’t include some food items. Whether in the chill of the Chin Hills at 8,800 feet, where I sleep in camisole+wool top+sweater+fleece jacket+pants+socks under three heavy fleece quilts and still am cold, or the hot plains where the devil’s breath blows on my cheek, his hot hands ruffle my hair and my eyes feel like hell’s cinders, I have been perusing markets. This trip more than ever I’ve found myself enchanted by colors and shapes, the unplanned patterns that create a beauty unrelated to the object itself.

Look at bananas…

Or fish, each dried in its particular identifiable shape…

Vegetables, fresh and cured….

Purple rice cakes ready to conjure into a morning meal….

Or bright yellow chickens in their red blood…

..next to related parts sought by the clever cook….

…every market fills me with such pleasure that I find it hard to leave.

But we are now in Yangon, ready to depart on February 16. Brunhilde has been delivered into MoeMoe’s capable hands and is presently resting, cleaned of dust and emptied of Snickers, in a dockside warehouse preparatory to shipping out on February 25. As I repack, I think of all the generous and welcoming people we met, drank tea with, talked to.

The lovely children, so tenderly looked after …

And the indelible images that Myanmar shared with me these past three weeks: Crimson spikes of poinsettias and luscious pink hibiscus… Soft grey mist shielding a roadside house and sleepy cows….

The music of wood bridges playing plick-squeak-thonk as we drive over the loose planks…air that smells of burnt toast and caramelizing sugar…..Stocky black water buffalos grazing near a field of nodding yellow sunflowers.

It’s been more than wonderful trip . Thank you for reading. If you still want to know the answers to the four riddles, here they are. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

1. She was being baconed from the other side!

2. He loved sow sages!

3. She herd the other side was better.

4. Pullet!!!

Posted in Burma Again, Dispatches

Leave a comment

Burma, uncharted

Tomorrow, February 13, is the 100th anniversary of the birth of revered leader Aung San, father of today’s Aung San Suu Kyi.

Though our trip was initially blighted by denial of our Ledo Road permit, we have been remarkably lucky since then. I have no doubt this is due to the fact we stopped at Yangon’s Sacred Banyan Tree for a blessing before we headed out. Everyone who buys a car in Yangon, or is departing on a road trip, stops at this nat, so who are we to deny the tree’s power. It’s January 23 when I place fragrant posies at the lip of the several shrines surrounding the roadside banyan, imbuing each gesture with as much reverence as I can muster. A flaring bunch of green and red leaves is tucked in Brunhilde’s radiator, a slender strip of red and white fabric tied to her rear view mirror. Then Bernard is instructed to move her backward and forward three times. There’s plenty of traffic noise and honking going on and soon I know why. As soon as he’s done with the final reverse, Bernard’s told to honk Brunhild’s horn three times as well. That about does it for the observances. We head

out of Yangon feeling sublimely protected from any possible harm.

As we drive we pass other road nat stations; at each we honk three times. And it’s worked. Because we’ve driven roads that are so vertical, so twisty, so far away from people, that if anything had happened to us or Brunhilde it would have been even longer before I was able to write this. Note please that the road department here has only two symbols to denote incline. The triangle part is placed at whatever angle will best impress upon a driver just what faces him. We’d been blessed, so I wasn’t at all worried when I saw this sign:

After all, the vehicle on it looked nothing like ours.

And besides, why else would we be able to drive to Aung San’s birthplace tomorrow, February 13, something completely unplanned and never even discussed before yesterday, if that the banyan hadn’t taken an interest in our well being?

Since I last wrote, our travels have taken us westward from Inle Lake, first to the ruby mines of Mogok, only recently opened to foreigners by special permit (a separate report on that after we’ve left the country). One thing I can tell you is that I was shocked, shocked, to see Johnny Depp in full Pirates of the Caribbean regalia, at Mogok’s full moon festival.

Here I was expecting thousands of devout Buddhists to be paying obeisance at the central pagoda. Instead we got a carnival midway, Myanmar style, with Angry Birds adorning inflatable slides and mini-BMWs transporting toddlers round a carousel.

Convincing our timid ministry minder, Kyaw, to join us on the pirate ride, we clutched the railing in front of us and shrieked in unison, while I silently hoped the ride qualified as a vehicle and thus was under the banyan’s protection.

As for carnival food: no funnel cakes or corndogs in Mogok. There were fried quail eggs, pancakes seasoned with sesame and coconut, ruby-red watermelon and plenty of tasty fried bits.

We’ve managed to include a couple of riverfront stays, to remind us of our sterling trip up the Chindwin River three years back. This year we were able to drive to the banks of the Chindwin through miles of young teak forest, on swooping empty roads, arriving opposite the town of Kalewa, crossing by ferry to the very docks from which our journey began last time.

I felt such an innocent back then, and feel such an old Myanmar hand now. I understand the food, love the customs, know what to expect in terms of hot water or lack thereof. We even got the same room in the same guest house as last time. I was pathetically grateful, though, that those chanting monks from three years ago had decided to take the night off.

We also put Brunhilde on a ferry to cross the Ayeyarwaddy from Tagaung to Tigyaing. We had plenty of time to observe Tagaung’s riverbank traffic, which bustled with trade: clay pots and cases of Mandalay Rum offloaded…

…replaced with sacks of charcoal for the onward journey.

I love the mild bustle of river towns, especially the market in the hours before dawn. In Tagaung, we caused mild hysteria wandering the candlelit fish aisles. Inspecting a bamboo platter of glistening silvery fish I pointed out to Bernard the flat mouth with long filaments streaming from each side. “Look, catfish,” I said.

Glancing over at the vendor I saw her thinking. I figured she was going to pose the standard, “Where from?” But no. She looked at the fish, peered into the gloomy middle distance toward Bernard, then pointing directly at his mustache, exclaimed “Catfish!” At that she burst out laughing, repeated “Catfish!!” and soon the whole line of fishmongresses were guffawing and pointing at Bernard, “Catfish!” echoing down the line.

West of the farming villages of the vast Ayeyarwaddy plains we entered the Chin Hills, which form Myanmar’s border with India. This is a place where the phrase, “Straight road,” does not exist, where some unhappy nat planted cobbles pointy side up and where dust never settles. Driving the Chin Hills made me long to have cartoon eyes. You know the sort I’m talking about: Eyeballs on springs, which can launch out of their sockets to peer around a corner to warn me if my body is about to collide with a moving object. Here’s the easiest stretch:

Villages along the way were one hut deep, each extending on stilts over near-vertical slopes. Of necessity, a lot of the living–whether pounding rice or babysitting one’s one-month-old grand daughter– took place right on the road.

Northern Chin used to be animist, but has been in the clutches of “real religion” for more than a century. It started with the Baptists at the beginning of the 1900s, who have been joined by a bevy of other churches, including Methodist, Pentecostal, Seventh Day Adventist, Roman Catholic and Evangelical. It’s truly startling to be asked “Are you Christian?” by a stranger at a village guesthouse. Somehow it seems too intrusive, like asking a stranger on the subway, “Are you a virgin?”

Our days in the Chin Hills seemed an eternity of jarring swerves around rumpled slopes and chaotic jumbles of ridges and gullies. At times I felt I was on a surfboard rising up to the curled lip of a Hawaiian surfing wave, plunging back down the face, and always more untidy green hills in front, crenellated ridges running in all directions like the fortifications of a crazy castle. Still, I wouldn’t have traded this tough portion of our drive for anything, as it brought us into a fascinating world. And our banyan tree nat continued to look out for us, keeping our tires strong and in one piece.

Even our untimed arrival in Bagan was filled with good fortune. As we approached the town of Nyaung U, a caravan of gaily decorated bullocks came trotting up the street, flashy flowered harnesses a-jingle.

If there’s one thing I know for a fact by now, it’s that bullock carts do not move fast. In fact, a bullock cart gives new meaning to the word slow. So what was causing the great bullock cart scramble approaching us? Why, it was a village novitiate ceremony, paid for by someone who’d evidently reaped quite the profit from his harvest. Parking the car off the road in a cloud of dust, we ran back to the large lot where music shrilled from loudspeakers and much bowing and praying by satin-robed women was happening on a mat.

Interspersed between them were fifty young girls, from three to perhaps ten, all ready to become nuns. This wasn’t going to be for a lifetime, just perhaps a week, but still, try asking a kid you know if they’d be willing to have their head shaved and go begging on the street for their food for a week, and see what answer you get.

Perhaps the youngsters who enjoyed the occasion the most were these young monks.

So here we are, leaving Bagan tomorrow for Natmauk, reaching Yangon as planned on February 14. In my next dispatch I’ll report on the celebrations honoring Aung San. I’ll show you why Myanmar’s markets are so inspiring. And I’ll reveal, without embarrassment, exactly what happens to my mind after hours and days of looking at village scenery.

Posted in Burma Again, Dispatches

Leave a comment

Burma, unscripted

In travel, timing is everything. And in our case, timing did not do us any favors. Two days before we arrived in Yangon, the Kachin Insurgent Army (KIA) decided to move its operations to the very heart of the jade mines west of Myitkyina, in an area called Hpangthong. That the Stilwell Road bisected their new territory apparently mattered not a wit. Not only was our permit for Myitkyina yanked, all permission to drive the Stilwell Road was summarily denied. So here we are, jouncing around the country with Joe, our cheery Ministry of Trade and Tourism minder, along with Saw, our ever-resourceful guide, seeing what’s to be seen, but not going anywhere near Kachin State.

As we ramble around in Brunhilde, making our plans day-by-day, we are learning first hand just how closed to foreigners Myanmar still is. Many nights we peruse our map with Saw. “Let’s go here, and drive this little road,” one of us says.

“Not possible,” Saw says, his face impassive, his dark eyes expressionless.

“Really? How come?” we challenge him. Politely.

“Opium,” he says. Or, “Mines.” Or perhaps “Rebels.” One road after another is off limits. If we can’t get on a particular road, then we can’t get to a particular place. And so it goes.

“But can’t we go anyway?” we wheedle. “We’re just one car. And it looks like a great road.”

“Cannot do.”

In some cases we can fly, as we did from Inle Lake to far eastern Shan State and a small city called KyaingTong, just 100 miles south of the China border. But flying isn’t the point of this trip, and when we’re not in our own car we start to feel as though an essential part of us is missing. So, after our brief foray eastward, we’ve decided to stay firmly on the ground for the remaining two weeks.

What I can report so far is that Myanmar is going through a tremendous transition. In the 3 years since we were here, tourism has increased from 300,000 to 3 million. Underpowered scooters that buzz like wasps, are everywhere. Traditional homes in remote villages, usually built of bamboo, are being replaced by cinderblock construction. The contrasts between traditional and contemporary, old and new, are everywhere. Yet I still see endless loveliness, even in such contrasts. Already I have so many visual memories I want to write a few of them down and also include as many photos as I think readers can tolerate.

For instance, there’s the local road crew carefully pouring hot asphalt from a can punctured with holes.

Plump, pearl grey Zebu bullocks plod along the side of the road between Yangon and Taunggoo, pulling a two-wheeled cart heaped with hay. In the hills above Mandalay it’s citrus season. We stop at a roadside stand to inspect mounds of honey-sweet tangerines and softball sized, brown-skinned avocados. We stock up on the former, leaving the latter for someone better equipped to deal with the slippery messiness.

After extricating ourselves from a road which rolled in on itself like a snake with a belly ache, we drove past a village school where a young boy in the green longyi of grade school leaped a yellow-washed wall to retrieve his woven bamboo soccer ball. The morning dew carries a heavy scent of musk, old urine and frying eggs, which makes me alternately gag and salivate.

Dropping down from the heights of PinLaung to Inle Lake, crinkled ochre hills turn into silvery outlines in the smoky haze.

As we get closer, we can see gilded white stupas which split the forest canopy like gold-capped sharks teeth. Tea break mid-morning is at a roadside teahouse, where stall merchants perch on tiny blue plastic stools, eating samosas and fried sweet dough sticks while watching Chelsea beat Manchester City in a Premier League match.

A woman stands at the edge of her swept dirt yard, negotiating the price of some sweets with a mobile vendor whose motorbike is festooned with cellophane packets glinting like a disco ball. I puzzle over the local anomaly of calling tangerines oranges and oranges Sunkists. Ang women still chew tree bark that makes their teeth shiny black.

Posted in Burma Again, Dispatches

Leave a comment