-

Archives

- November 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- November 2015

- February 2015

- July 2014

- June 2014

- October 2013

- January 2013

- October 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- November 2010

- September 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- March 2009

- February 2009

- March 2008

- February 2008

- November 2006

- August 2006

- March 2006

- August 2005

- July 2005

-

Meta

Daily Archives: February 28, 2015

Rubies Are Red, Sapphires Blue

Some See Rubble, Others Riches

“I’m frightened!” Saw blurts, his dark eyes seeming to strain to focus on something far behind my back. Detecting alarm on my face as I try to decide if I should be concerned, his shoulders start to heave, his head nodding in staccato bursts. Saw is throwing a major laughing fit.

“Last night,” and he nods abruptly again, as if to confirm this really happened, “I’m awake. Very dark! 3a.m.!” Saw speaks only seldom and when he does it’s in compressed sentences, with extra emphasis on every one, as if each is a declaration of global import. He also often repeats himself, in part, I think, to make sure his foreign listener understands, and in part, perhaps, to confirm to himself that he has, indeed, said something out loud. “3a.m.!!

His nodding shifts to double-time, betel-stained teeth visible in his wide open smile. “Feet gone!” He pauses for maximum effect, leans forward, his eyes boring into each of us in turn. “Stolen!”

Here he utters one of his place holder pronouncements: “So?”– a rhetorical inquiry to give himself time to formulate the next part of his story in English.

Looking around wide eyed, Saw says, “I think, ‘Ghost took them!’ He glances at each of us as we search warmth from a small china cup of tea in the open air of a chilly Mogok teahouse. “Ghost!! So? I’m frightened….because…..no feet!!”

Now he has to set down his teacup because he’s laughing so hard, shaking his head in disbelief. “Last night too cold!”

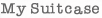

Mogok, a prosperous mountain town of low-rise houses and plenty of monasteries, sits at 1000 meters. It’s hot enough for a tank top and sandals during the day, cold enough for cap, wool top, sneakers and fleece jacket at dawn. The hills that rise from the town are salted with stupas, their covered access stairways hugging a ridge like scales on a dragon’s back. Beyond the stupas rises a ripple of higher forested ridges, the green canopy dotted here and there with a tree in effervescent lavender blossom, or a tall shrub flowering in a froth of white. Look closely and you’ll notice large patches missing from the forest, as if a green scab had been scraped off, revealing the raw, pale orange earth beneath. These are the ruby mines, from which over 70% of the world’s rubies are extracted, mines where rich veins of quartz are dynamited far below ground, to release tons of commercial grade gems as well as jewels of the

rarest size and quality.

As some of the first foreigners with permission to enter Mogok, we are the lone whites on the bustling streets. Our first stop after Saw’s comedy routine is the Thar Phan Bin gem market, on a narrow side street near the town’s central roundabout. This morning, because of the cold and because it’s midway through the Full Moon Festival, most of the shop doors remain closed, the small time opportunists absent. Most buyers and sellers are elsewhere, either recovering from the 3:30a.m. prayers at the main pagoda, or preparing for the coming night’s festivities. So we drive out of town, to the mining village of Ka Doke Tak. The route takes us up into those forested hills, past small clusters of teashops at which scooter-riding ladies stop for a neighborly chat or to pick up the day’s necessities at the local ‘grocery store’.

The pale dirt streets to the mines of Ka Doke Tak wind steeply up from the village’s market place, host most days to a TAR PWE ( which means brass plate on which gems are displayed), the informal street market where successful scavengers sit on low stools unwrapping squares of notebook paper to show the tiny raw gems they’ve chipped from quartz waste deposited by each mine in truckloads, free for anyone to pick through.

Most are women, who may quietly draw up alongside a stationary visitor to show a few pinkish-red grains, or perhaps a lump of quartz….rubies in their raw state.

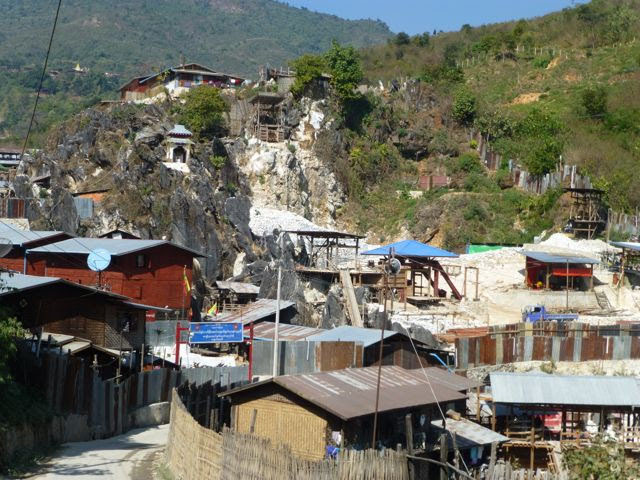

Along the road up to the mines, women squat on piles of sparkling white quartz, faces shaded by conical bamboo hats. Each woman has friends who work the slap heap with her and each such group has its designated pile, just as a drug dealer would have an acknowledged street corner, upon which others do not encroach.

The women are Lilliputs squatting on Gulliver’s giant pile of sugar, except the quartz gleam is brighter, harder, denser. With one quick movement a woman carves out a small heap with a piece of tin, checking through the seed-size grains with nimble fingers, as if searching for nits, then drawing in another mound. Every day more is dumped, a snow white pile of endless glittering promise.

We try for our first unannounced mine visit. The one we choose. Saw tells us, is operated by the Chinese. Its high, heavily dented tin gate under a flag-sporting archway, blocks our view of the yard inside. Razor wire discourages clambering over walls. As we lurk hopefully near the entry, a security guard unlocks the gate for an approved person, but clangs it shut for us. “Not easy here,” says Saw, more expressively than usual. “Chinese owners,” he continues quietly. “Not want you see.” He clasps his hands behind his back and ambles up the road.

But I’m still curious, so I linger behind. On either side of the entry gate are two newly built watch towers, just like on Hogan’s Heroes. They’re empty, though the arc light in each implies they may be manned at night to prevent thievery. When Saw saunters off I dare to peer through a hole gashed in one gate panel. I can see an orderly dirt quadrangle, with men under tin-roofed sheds squatting in front of piles of ever smaller pieces of quartz, the essential material in which rubies, and sapphires, are found. I hurry to snap a photo.

Perhaps the little zoom lens of my camera, which I’ve shoved into that hole, betrays me, because through the view finder I see a man in camouflage pants quick-stepping my way. I do my own quick step up the street to rejoin Bernard, palming my camera into my pocket, feigning interest in the view ahead.

In one mine, 17 men report for work every day. Seven stay on the surface doing an assortment of support jobs. Two squat on a grey pile of explosive compound, which they sift into dynamite tubes and top off with detonator charges. By hand.

The mine’s working surface is a cobbled-together wood platform with two 5’x7′ openings, each with a pulley system and cables descending into the black. Twenty feet below this platform a ten-rung wood ladder made of limbs and branches is visible, the first of many such that a miner will scale each day to get to his designated level. It’ll take him 20 minutes to descend ladders to 1000 feet, perhaps double that to clamber back up.

Down one go a quartet of black buckets full of concrete, to be returned minutes later for a refill. Up the other comes a quartet of black buckets to be filled with quartz rocks the size of footballs. Two two-man teams staff these portals, through which rock is uploaded from the ten lateral tunnels bored at 100-foot intervals below and cement is download to reinforce those same tunnels. Four buckets come up at a time, are detached from the pulley and lugged to a truck 10 yards away, where the contents are dumped into the bed. Not more than 5 minutes passes between bucket arrival, detaching, dumping, reattaching and sending the bucket ensemble back to the depths. The buckets arrive every ten minutes or so.

The shift supervisor, Ko Nan Mg, grew up longing to work in the mines like his father did. He tells us he remembers peering into the mine where we’re standing when he was six, wishing for the day to come when he could join the men behind the gate. Now he’s thirty, and has done every job this mine has to offer. A man tends to start at the mine around age 16, and if below ground, will be in an environment in which water drips continuously, to such an extent that during the April to October rainy season the mine shuts entirely. Barring accidents, he may work at an assortment of mine jobs for 45 years.

These are not bon-bons…..

While we talk with the supervisor, the mine’s manager sits nearby, playing with a litter of puppies. A fuzzy black and beige one clambers at his pants leg. Slowly placing his hand under its plump belly, he scoops it up gently to his face, kisses it on its black nose, sets it tenderly back with its mates.

Further up the road, a young man stops his scooter and steps into a narrow paved drain which carries the shallow bluish sluice from a mine above. He scoops out a light handful, spreads the grist on the wall beside him and quickly stirs through it. Nothing. He scoops, dumps, spreads, stirs again.

Above, behind a 20-foot tin and bamboo wall, a Chinese track hoe shovels bucketfuls of quartz rock into an immense funnel. The rocks bang onto a conveyor belt, rattling along to a crusher, smaller pieces clattering onto vast mats on which sit sorters, checking all, removing a few, pushing most over the edge into the rejects bin, from where dump trucks will bring them to those favored street corners, for the unemployed to sift through.

Returning to Mogok mid-afternoon, we order fresh avocado juice (for me) and beer (for the others) in a cafe brightened by shelves of potted petunias. It’s a happenin’ place and the terrace up top is packed with clusters of teenage couples gesturing with cell phone in hand. The place has the air of a 1950s soda shop, except the muscle cars are motor scooters and all the occupants are Burmese. Even though it’s 3pm on a hot sunny afternoon, the girls are in long slinky dresses and furry pink jackets, hoods tied by pompoms a cheerleader would envy. The boys wear skintight jeans and Converse knock-offs. Their T-shirts betray the local maker’s incomprehension about the world outside Myanmar: Real Chelsea, Harley University, I ‘heart’ Hello Puppy. Each sports the latest mountain town pompadour, complete with a russet swath tinted into their black hair.

Most of the boys drape a possessive arm around the girlfriend du jour, who snuggles with acquiescent delight. Noodle soups and curries arrive, and the boys fall to, while the girls pick daintily at a morsel, suck from a straw standing upright in pink sludge which must be a strawberry shake. They hunch forward shrieking with adolescent laughter, collapse back against the protective side of their boyfriend to catch their breath.

Back on the mining village corners, the quartz heaps beacon, the sifting continues. Because in Ka Doke Tak, one may be poor for a lifetime, but rich in a day.

Posted in Burma Again, Dispatches

Leave a comment