-

Archives

- November 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- November 2015

- February 2015

- July 2014

- June 2014

- October 2013

- January 2013

- October 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- November 2010

- September 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- March 2009

- February 2009

- March 2008

- February 2008

- November 2006

- August 2006

- March 2006

- August 2005

- July 2005

-

Meta

Monthly Archives: November 2017

Rajasthan… Rats

Bernard came out of purdah…

… at Ghanerao Palace, near Narlai, in the countryside south of Khumbalgarh Fort.

Why fling open the carved stone lattice screens to taste the winds of freedom on his face? I suspect his gesture was born on the breezy sandal-clad feet of the confidence he’s gained drinking cup after minuscule cup of Masala chai. This is something new for Bernard, who for reasons he’s kept to himself has never deigned to take more than one, wrinkly-nosed sip of my favorite beverage.

I’d like to take credit, and say he’s followed my lead, impressed that I’ve never gotten sick regardless whether I’m sipping a tiny plastic cup at a street stand, or slurping from a saucer offered by a hospitable couple in the countryside, the milk no doubt taken from the steel canister in the shade, holding the morning’s deposit from the family Tharparkar (the gentle humped Sindh cattle breed seen all over Rajasthan).

But I think the truth has more to do with his despair at the awful coffee on offer.

There has been another delightful surprise this trip, to do with animals in pet form and my contact with them. Normally in India it’s all about sacred cows and pariah dogs, and the general need to give them all as wide a berth as traffic and garbage heaps allow. This trip I had personal time with a large range of pets, and it was a real boon to my spirits. Yes, I photographed many of these sweet animals, if only to show that travel in India isn’t always about gorgeous ethnic dress, fabulous ancient forts, exquisite gold nose rings and winsome children. In truth, as I travel, the more puzzling the questions encountered each day, the more ordinary the scene at day’s end needs to be. And the more vibrant the interaction, the more I long for whatever simple thing will speak to me of home.

It all started in the Kutch where we were welcomed by the joyful prancing of Astro, young German shepherd rescued

by a staff member who found him starving on the road.

Astro had two yellow Labs for company, Max and Maya, the latter disappearing for hours to nurse her littler of month-old puppies, who were just as warm and squishy soft as they look!

In Dasada, Gujarat, our lodge had 4 Persian cats just like Blofeld’s in the 007 films, as well as 5 dogs. The cat who snuck into our room was a mother seeking some ‘me’ time—or maybe that should be ‘meow’ time— from the three kittens she’d birthed in a brass urn three days prior.

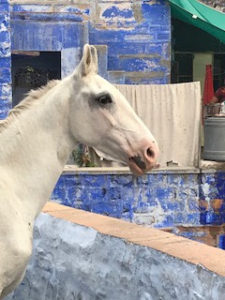

I also got to snuggle with an uncharacteristically quiet beagle and a strangely lethargic Saluki. Dasada had an impressive stable operation, which included some Kathiawari horses, one of which I got to ride. Unlike the Marwari, the Kathiawari are small, averaging 14.2, with a pretty rather than noble head. Riding one is actually a bigger deal than you might imagine, because the breed is slowly dying out, not having attracted as much attention as the Marwari which I mentioned in the previous newsletter.

It was quite a stunner to see the care (and special feed) lavished on the horses. In some ways, with so many people in India having so little, it was off-putting. But I don’t pass eery day of my travels in passing judgment, so I’ve stored away my observation of the huge buckets of grain prepared for every horse, mixed with lashings of molasses, corn oil and minerals, for later digestion. And decided in that particular moment it was just a pleasure to see animals well-cared for.

And of course there was our memorable stay at Jodha stud farm, surrounded by mares, stallions and their output— foals, ….

as well as sweet Tyce the Doberman and his lady Rottweiler pal.

Marwari typically make their living being in wedding processions, and though it’s not required, people do like to have white ones for that. Wedding processions are loud. And I mean LOUD!!!! as in “What did you say????” loud, with banging drums and chanting projected across kilometres (or so it seemed at night in our hotel). One day in Udaipur we came upon one and joined the crowd of family and friends accompanying the groom on his white steed. Of course I immediately felt sorry for the horse, wondering if he’d been given early retirement due to hearing loss, until I noticed his ear protection. Take a close look and you’ll see:

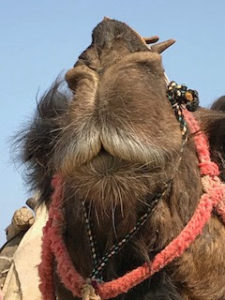

So things on the domestic animal front were pretty swell. They weren’t so bad on the work animal front either. Our camel cart bull knew how to nap with the best of them, but instead of folding his legs under himself neatly, he sprawled full out on the sand in a good imitation of “Dead to the world,” as soon as he was unharnessed.

There was a new sight for me from mid-Rajasthan onward; the feral pigs rampaging around certain towns. Even those Hindus who eat meat now and then eschew pork, so why are there pigs running around? Turns out it’s someone’s bright idea of a way to get rid of more of the street garbage. Thing is, the pigs aren’t neutered, just as street dogs and bulls aren’t neutered. So the pigs are breeding like that other barnyard animals, rabbits, turning aggressive and sporting bristles on their back that put Bernard’s shaving brush to shame. We’d see people chasing them out of the yard with a broom, keeping a good distance in case one dissented. Monster sows with full teats were trailed by piglets, in turn shepherded by the adolescent, already-weaned, generation. And I don’t want to go into the sight of a feral boar rooting around in the heaps of soiled rags and plastic.

And then there are the black rats. I’m talking about the 25,000 that call Karni Mata Temple in Deshnoke, home. These are holy rats —kabbas, and many people travel great distances to pay their respects, as did we.

First rule before entering any temple–even one not especially pristine—is remove the shoes, which I did, refusing the reusable muslin foot coverings other–I’ll call them the squeamish– were taking. I felt brave about that. Then I approached the rat gift cart, as i didn’t want to enter a place swarming with rodents without something to distract them, should I need to. The vendor handed me a plastic tub of wrinkled yellow pebbles. Dried chick peas to me, apparently a welcome treat to a rat. “Favorite, favorite” he assured me, in that Indian way where doubling or tripling a word adds strength to the sentiment. As though I might ruin my karma forever if a rat didn’t like my offering.

I put aside my gag reflex as I padded barefoot across a white marble floor tacky with rat pee, centuries of it. I notice one thing immediately: the rats are not black. They’re a uniform ratty brown, with rather ratty coats, regardless that they have a 24 hour buffet at their disposal.

Once the temple entrance is breached I approach the sanctuary the goddess with my little plastic tub and great feelings of general piety. So I am mildly fussed to be turned abruptly away. The silver doors open for the faithful only. And those faithful are arriving with brass bowls heaped with orange marigolds, some with a golden box of premium Indian whisky or rum under each arm. What I secretly think is, “Who’s drinking all that liquor?” Followed by, “This goddess is my kinda gal!”

I shuffle off around the shrine, past large basins of milk with rats delicately sipping as they cling to the rim. One or two can’t be bothered with such politesse, choosing to wade right into their drink. A furry creature scuttles toward a hill of millet, brushing against my foot before rebounding away in a new direction. I mutter about “sacred who cares” as my sticky soles squelch rat droppings. Around the corner a handful of satiated rats frolic and tumble, dancing on hind legs and somersaulting. When I see a rat stagger across the marble courtyard, likely in the last throes of some contagious ratty démentia, I decide it’s time to leave.

There were even some bird interludes on this trip, like the miracle of seeing hundreds of migrating Demoiselle cranes at Kheechan, where for 150 years villagers have been offering them bribes in the form of plentiful grain and a little lake, so that they return every winter. The ones we saw likely flew in from Mongolia or China, and they were gorgeously regal birds to watch, which we did in the company of a number of Kheechan villagers who daily come to check on ‘their’ birds.

You can probably tell that my interaction with animals on this India trip has lifted my spirits immensely. That is until the afternoon I was wandering an old city neighborhood and from somewhere on high a pigeon pooped on my head. It really did. And there’s nothing more to say about that.

Posted in Dispatches, Gujarat and Rajasthan 2017

Leave a comment

Rajasthan… Reveries

Is it possible to inhale…

…….and exhale at the same time?

If a place can be a question then the above one would be Rajasthan, a land full of opposites, often seeming blithely ignorant of its own contradictions.

Hugging tradition while courting development. Cities choking on plastic and fumes connecting to hamlets where peacocks and chinkara gazelle wander through clean sandy courtyards. Strangling in a web cinched ever-tighter by motorbikes and cell phones within a vast, tranquil emptiness.

What follows are a series of postcards of the deep impressions of my time here.

Desuri, Marwari, Jodha Stables

As the sun subsides to the horizon, a yellow sigh in a silver soft sky, five women pick cotton. Pink, magenta, lavender, emerald, flame, ruby, their saris burble through the dense green foliage. Lime green parrots flit among the heavy-limbed banyans, shrieking, fluttering, alighting only to take off.

Lithe village dogs, tan and taut-limbed, leap from slumber so deep not even the wheels of a motorbike at their toes disturbs them. That is till now, when we, 3 riders on fine Marwari horses, accompanied by a Rottweiler and a Doberman, walk thru their village.

Howling in outrage they bristle and bare teeth. They mock charge with false bravado, skidding to a halt in puffs of dust, making sure they are well out of range of a horse hoof.

Lest you feel sorry for these dogs, feeding them is a virtuous act; I see old women and working men leaving offerings for their favorite dog(s) everywhere.

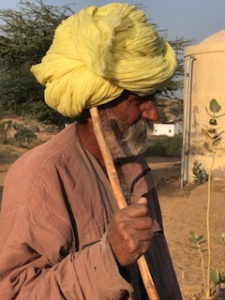

A peacock struts a brown field already dotted by the winter’s crop: tender green shoots of cumin. While others in the family till the soil, a man sits quietly at the edge of a field of green cane stalks, legs crossed in the lotus position, a bulging white turban shading his thin dark face. He turns to watch us, revealing a flamboyant bristle of white mustache.

One hand holds a walking stick. The other raises in slow salute. A bare warm breeze carries with it a baby’s cry from behind a stone wall, along with some half sweet half herbal smoke from the family’s cook fire.

Jodhpur’s Sardar market

15:00 on a hazy mid-November Saturday and the plaza circling Jodphur’s clock tower is humming like a beehive in overdrive. It’s the day of the new moon, a holiday for which all factories are shut, and now those 1000s of workers on one-day holiday have come into town for some shopping. I’m at the hub of Sardar Market where today everyone’s dressed in their best, second, third or fourth hand though it is, as betrayed by the ragged edges and frayed hems on shawls and shirts, edges so frail they no longer can hold a mending stitch.

Couples and small families, thin, dark skinned, with sharp features and serious gaze, wander among tables groaning under bins loaded with plastic sandals and Chinese sneaker knock-offs, past wood push carts densely fringed with men’s belts, along tables groaning under pyramids of gaily colored bangles. But the true focus seems to be what’s in front of me: the used sari vendors. This 30’x50’ street plot holds 20 female vendors planted like shrubs among the fat bundles and piles of bright cloth, their kids playing along the perimeter and a handful of toddlers flung onto the soft warm piles of clothing, asleep in the sun.

Our walk through some of Jodhpur’s blue neighbourhoods has brought us to the square.

And from that ramble I can parse the smell in the warm air into the light smoke from the home small fires burning the night’s refuse, the sweet rot from squashed vegetables mixed with manure, and petrol fumes from the hellish tangle of motorbikes and auto rickshaws clamoring through the plaza dodging shoppers and gawkers like a matador avoiding a bull’s horns. And with just as deadly results for any miscalculation of speed, direction or intent.

There’s an air of pleasure and excitement mingled with purpose, as shoppers husband their hard earned savings and husbands eye wives eyeing a new sari. The women plunge up to their elbows into fabric heaps as bright, colorful and scintillating with sequins as a box of Christmas ornaments. They’re intent on a color or design or fabric known perhaps only when they see it, and they’re willing to sift patiently and shake their head politely until the right 9 meters of cloth appears. The 30 rupees they will part with for a used sari (50 cents) is hard earned and long saved.

A girl of ten or eleven, scrawny, in baggy leggings and a frock two sizes too big, sports a new barrette, green and curlicued, in her dusty and sun bleached ponytail. The pleasure of her new adornment is obvious as she stands by her mother, fingering the ornament she cannot see. Her mother wears a heavy pink flannel car coat over her daffodil yellow sari, shyly holding a red sari a-sparkle with gold threads up to her chest for her husband’s input. The girl herself won’t wear a sari till she marries.

There’s a continuous cycle of unfurl, hold up, query and discard going on. Here a sari the color of a peacock’s tail, there an olive grove in summer, another like a box of saltwater taffy, or a raspberry crumble. A husband in a pink shirt, his head wrapped in a green and grey cloth holds a nubbly midnight blue sweater to his chest for his wife’s approval. Next to him an older man grimaces, red-tinged tufts of white hair spiking from under the dun scarf tied around his head, his sharp shoulders wrapped in a once handsome olive shawl shot through with yellow and black diamonds. It’s tattered, a large tear in the back, some edges more than frayed. He holds a shopping sack laden with purchases while his wife, dressed in dayglow pink sari embroidered with silver daisies, lifts options for consideration.

The vendors need sustenance but no one has time to leave their heaps. So the chai walla weaves through the crowd with a thermos and stack of tiny paper cups, flirting with a smile or head waggle as he pours.

Voices rise and fall like the cry of seagulls when a fishing boat comes into harbor. Motorbike horns cheap and caw in vain for attention from pedestrians preoccupied with more urgent business than stepping out of the way. And then a hand disappears into the top of a sari blouse, as if to scratch an itch. But it comes out holding a thin wad of folded bills from which one or two are peeled off and dropped casually on the nearest pile. A deal has been struck.

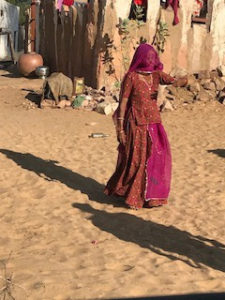

Hacra

We stayed with a family in Hacra Dhani, a farming community in the semi-desert near Osiyan. The days there were sun-filled, the cold nights blazing with stars. Whether by camel cart or on foot, we ventured from home to home, moving at nothing faster than village pace.

Everywhere we sipped chai, till even I had to refuse the last cup offered, so awash with milk and spices was I. I sat with the women of a Bishnoi family while Bernard regaled their men with stories.

Millet and peanut harvests were already in their little storage huts, cotton ready to pluck, and castor beans ripening.

The farmers are doing well, as evidenced by the heaps of red granite blocks piled in front of each compound, ready to build big square houses to replace the large round mud&daub thatched huts of yore. We provide distraction for a family of camel herders moving rocks for their new home. They’re curious: Does America have a caste system?

At the home of a weaver, 18 children crowd into the carpet weaving hut to observe us. The shy turn away and break into fits of laughter if we get closer. A few braver ones practice words of English and urge us to take their photo. Over and over. And over.

Jaisalmer

In the early morning hours we make our escape from the reeking, hellish congestion of Bikaner’s narrow old quarter, intent of getting out of town while the city’s 500,000 motorbike owners are still abed. We’re glad to be on the open road, passing the usual assortment of ungainly vehicles, waiting patiently with everyone else at the ever-present railroad crossings.

A guard wrapped against the morning chill stood at a factory entrance, his hand resting on the head of a three-legged pariah dog. Both stare vacantly into the distance, perhaps at the ceramics and brick factories whose smoke stacks pierce the horizon like porcupine quills, each streaming a long grey lag of smoky effluent. The drive is a bone rattler, the pavement so chewed up in places its as if cows during their lean months had taken bites out of it.

From Phalodi to Jaisalmer the desert grew more bleak with factories and the weedy acacia thorn trees. Camels were supplanted by more contemporary ships of the desert: camouflage caravans of heavy military trucks, lumbering nose to tail through the desecrated desert. Their fifth wheels are shiny with grease, ready to attach to trailers transporting … missiles? …tanks? into position somewhere, for something that portends no good. We zip past an Air Force base, with a gate over which the company logo is displayed in meter-high gold lettering: Strike Hard, Cut Deep

And finally we reach the beauty of Jaisalmer, a small blocky town which wakes reluctantly in its brown morning haze, hunkered below graceless yellow water towers. Above is the fabled fort, ten centuries old, its color a dreamlike blend of amber and butterscotch, clover honey, crème caramel and saffron. Walls undulate and ripple, a shimmering mirage of faded ages. It appears to rise and subside simultaneously, at once surmounting the crumbled slopes below and inexorably drowning in them.

It’s a mirage, except those are the tandem fighter planes, like roaring quotation marks, on routine fly by of the India-Pakistan Border a mere 80 miles away.

It’s been a tremendous trip. Like this little rat at Deshnok Temple, I feel like I should go find someplace tranquil, uncrowded and not moving, for a long snooze.

Okay, breathe out now. And to all those who are not presently in India eating curry, Happy Thanksgiving.

Posted in Dispatches, Gujarat and Rajasthan 2017

Leave a comment

Go… Gujarat bonus

There’s more to Gujarat…

… that I thought you’d enjoy. Especially now that I’ve figured out how to get certain photos to upload. There’s this: that the water buffalo in Gujarat are not the run-of-the-mill sort you see elsewhere. They’re a breed from the Banni Grasslands, called, appropriately, Banni buffalo, and they give an inordinate quantity of milks a day: 11 litres! The way you can tell them from the others you see around the world are their tiny, tightly curled horns, as if they’d just gotten a stiff perm at the beauty parlour.

Apart from that, they’re like water buffalo everywhere: lovin’ their time in the local pond, like this one at Dharampar, near Lodai in the Little Rann of Kutch.

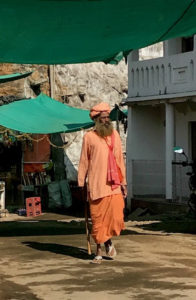

Here’s another interesting tidbit I learned, after days looking at herds of zebu cattle being walked to and from home by a single herdsman or two, like this stately gentleman.

Thanks to our numerous impromptu village walks I know that most families have only a few cows. Yet we’d pull to the side and choke on the dust raised by fifty at a time. And they were mainly all grey. So how did each family recover its own animal or three at day’s end. Well, for every question there’s a simple solution. In this case, they paint their horns.

On the salt flats of the Little Rann of Kutch, we had tea with a salt farmer as the sun set. He was living with his wife and teenage daughter in the middle of the flats in a makeshift one-room shelter of yellow plastic tarps stretched around branches, They, along with their two labourers, were onsite for the 6-month season of salt harvesting, which starts at the end of monsoon, so around October, and ends with the start of intense summer heat, so around April. During the harvest season he’ll pump the saline water from its 70′-deep aquifer; from that source it will flow through narrow, shallow hand-dug channels to the drying ponds in front of his hut.

After air-drying in successive drying ponds, the last step will involve manual labor, in this case provided by two ragged men whose job is to tug a heavy stone roller over the final drying pond, to squeeze out the drops of remaining moisture, yielding salt crystals the size of large gravel which I showed you in the prior dispatch. In a successful season our salt farmer will harvest 600 tons of salt, which he’ll sell for 200 rupees per ton (a US dollar equaling about 65 rupees), grossing 120000 rupees, out of which he may pocket half after expenses.

I have been staring (despite the disapproval of a certain someone) at the beautiful, and sometimes copious, and definitely weighty gold earrings of the different tribes.

When we were with the semi-nomadic Maldhari tribe in the Banni Grasslands of the Great Rain of Kutch I noticed the 9 and 10-year-old girls already had quite an array of earrings.

A married woman will have even more daily finery.

But then I saw a young woman with a 3-year-old on her hip, next to an elderly woman, both without any ear adornments and missing the bangles which rose over the biceps of other women. I asked why and learned that when a woman is widowed she removes all her finery. I could understand why the elderly woman was widowed, but something tragic had happened to the young woman’s husband, a story about which for once I didn’t dare ask.

Well enough of that. I’ll close this Bonus Dispatch on Gujarat with this Rabari shepherd, wearing the traditional skirted white jacket of the tribe. We met him when he brought his herd of sheep and goats to the water buffalo pond for a sip.

And now we really are off into Rajasthan!

Posted in Dispatches, Gujarat and Rajasthan 2017

Leave a comment

Go… Gujarat!

It took me less than four days…

…to make my first faux pas in India. I was at Palitana, on my way down from walking up the 3600 steps (3900 depending on your source) to the reach the 863 (900 depending on your source) temples on the summit of Shatrunjaya hill, considered the most sacred pilgrimage place by the Jain community, a place every Jain aspires to climb once in his or her life. As an aside to my terrible tale, you need to know that a central tenet of Jainism is not to kill any living thing. In fact in 2014, Palitana became the first city in the world to be legally vegetarian, making illegal, the buying and selling of meat, fish and eggs, And in further fact, Palitana had just reopened after its 4 months closure during monsoon, when a stair-climbing pilgrim would have risked squashing untold insects.

So there I was, about half way down, when I crossed paths with a solitary gentleman who pointed to a nearby stone tank, one which I had happened to peer into, just out of curiosity, on the way up. And when I did I noticed the largest, fattest toads I’ve ever seen, lurking in a sliver of shade on the moist mossy bottom step, just above the brackish opaque water at the bottom. So when this gentleman pointed to the tank I made a pleasantry to show I considered us fellow stair climbers, as follows`”Yes, it’s a lovely catchment tank. And there are large toads in it. Maybe we should have us a little barbecue?”

Bernard looked at me with a startled face, as if one of those toads had just plopped down on my head. Too late I realized what I’d said. I cannot describe the look of forlorn dismay my bit of tired uncensored wit generated. I can tell you I skipped as swiftly down the next section of steps as my shaky legs would allow.

Since then I’ve been as careful as possible. I’ve let anyone smear my head with as much or as little turmeric paste as they wanted, My sandals have come off in front of every doorstep and temple, even when I’ve been urged to keep them on.

I’ve acknowledged the little Lakshmi feet inviting prosperity to cross the threshold of homes and shops,

as well as the threads binding peppers, lime and charcoal to ward off the evil eye.

The first half of our trip has taken us through Gujarat, a state unlike any other we’ve been to. Daily the sky was a pale hazy blue, the air hot and filled with dust and smoke as fields of cotton or bushy green castor bean plants (a major cash crop of Gujarat) were harvested, hay piled high on trucks to trundle down lanes in between fields. Toddlers were watched by grandfathers as parents swathed and stacked large bunches of dried stalks for cattle fodder.

In Anand, home of the remarkable Amul dairy coop, instead of having one or two thin cows, families seemed to have 6-8 beasts, all of them sleek and healthy.

Driving across the state the roadways lined with mammoth manufacturing plant, but as we got deep into the Rann of Kutch, both Greater and Lesser, we saw pale sandy ground arid land overgrown with thorny acacia, the product of a misguided government attempt to delay desertification by dropping seeds of this non-native species from airplanes. Without anything to eat it (no giraffes or elephants here), the shrub has evicted most everything that’s native, leading to hundreds of miles of inedible plant-life, which in turn does no favors to the water buffalo and cattle herders.

Yet the essence of what I love about India was evident every time we stopped to walk around in a small village somewhere off the main road. A polite inquiry as to where we could buy a cup of chai would inevitably lead to an invitation to someone’s house. Word would spread quickly, and teachers, relatives, children, whoever was available and otherwise unoccupied, would come over to look at us. And to take selfies.

Sometimes communication would be simple, because a local son, visiting from college, would come to talk and translate. Other times communication was with a smile, headshake and laughter. But it’s easy to understand that cupped hands moved to the lips mean Chai and fingers pinched together, also brought to the mouth, mean food. Burning hot milky tea spiced with ginger would appear, poured into saucers so that it would be sippable quicker. All the men would have tea with us, but never the women, who hung back at the entrance to the kitchen no matter my entreaties.

Tea properly drunk, we would then be asked to stay for lunch. This would be a sharing of whatever our hosts were eating, such as some fresh roti with ghee and a bowl of soft, rich, slightly sour water buffalo milk cheese in Dharampar near Bhuj, or hot thin chapatis with a little bowl of spicy yellow dal heavy with cumin seed in Salwagada, south of Anand, or even a platter of charred peanuts with a bowl of green beans at a self-styled ashram in Devgana, near the soon-to-be embarrassing Palitana.

In the Banni Grasslands of far west Kutch, we were welcomed by an extended family of Maldhari nomads. Backed by a brilliant orange lowering sun, the heavy bulk of black water buffaloes shambled through the scrub toward camp. Tea came from a nearby fire, poured into the ever-present shallow saucers, and a small remuda of fit Marwari horses loped in to join the Zebu cows in the camp enclosure. Children squealed and played with our cameras, the men came ’round to chat with our friend, and behind us was the slap and punch of dough being pounded, from which balls would be pinched and flattened to make roti for the evening meal.

Bernard has been doing a great job of driving, but reports his impression that what’s happening on the roads situation has gotten worse. I differ. It’s as chaotic as it’s always been, still a wild, unpredictable stew of slow and fast, big and small, animal and mechanized, noisy and noisier.

Our vehicle, a Toyota Innova Crysta, is a bit too large for our liking, but in that sense does offer extra protection. Also on the plus side are its Delhi plates, which means no one cuts us any quarter, leaving Bernard to snake through traffic like the native he’s thought to be, and me to stare fixedly at our GPS, spouting lefts, rights and straight ahead at the roundabout with as much sangfroid as life inside a pinball machine with the flippers on overdrive allows.

Writing these newsletters is not just about putting a few impressions into words. They allow me to reflect on what I’ve seen and done, to form connections where earlier I’d seen just jagged pieces with no semblance of a whole, simply to step aside from the daily efforts of figuring out where to go and how to get there, all the while absorbing the extraordinary amount of shifting stimuli around me. By so doing, I suddenly see the simple interest, kindness and humanity in our daily encounters, each an individual bead which, when threaded together, form a bracelet of loveliness and warmth which replenishes my energy more than you might imagine.

We left Gujarat yesterday, eager to search out the fabled beauty of Rajasthan, its northern neighbor. A dramatic drive to the southern hill station of Mount Abu brought us to a climate zone full of tall trees, with flashes of magenta and pink oleander. At the summit, around the Dilwara temples, sprightly monkeys added their antics to the traffic problems and fringed palms towered above tangles of bougainvillea, while at the mountain’s base, camels used the national highway for their slow and always stately progress. One doesn’t honk at a camel cart. They barely move anyway.

Posted in Dispatches, Gujarat and Rajasthan 2017

Leave a comment